When you picture the Mediterranean’s blue economy—encompassing its vibrant fisheries and aquaculture—what’s the first image that springs to mind? For most, it’s a classic scene of fishermen hauling nets on a weathered boat. But if we widen the lens, a more complex narrative comes into focus. From the lively fish markets of Egypt to the extensive coastlines of Morocco, it is women who are the quiet powerhouses driving the post-harvest economy. Their roles in selling and adding value to the catch are nothing short of pivotal.

Yet, their immense contributions are frequently overlooked, consistently underpaid and hindered by systemic barriers. As a researcher in gender and social inclusion, my focus has always been on how we can amplify women’s voices in blue entrepreneurship. This personal quest found a new dimension through my participation in the Mediterranean Youth in Action (MYA) programme, ultimately crystallizing into a critical question: how can we forge a more resilient blue economy to empower women meaningfully?

Why It Matters

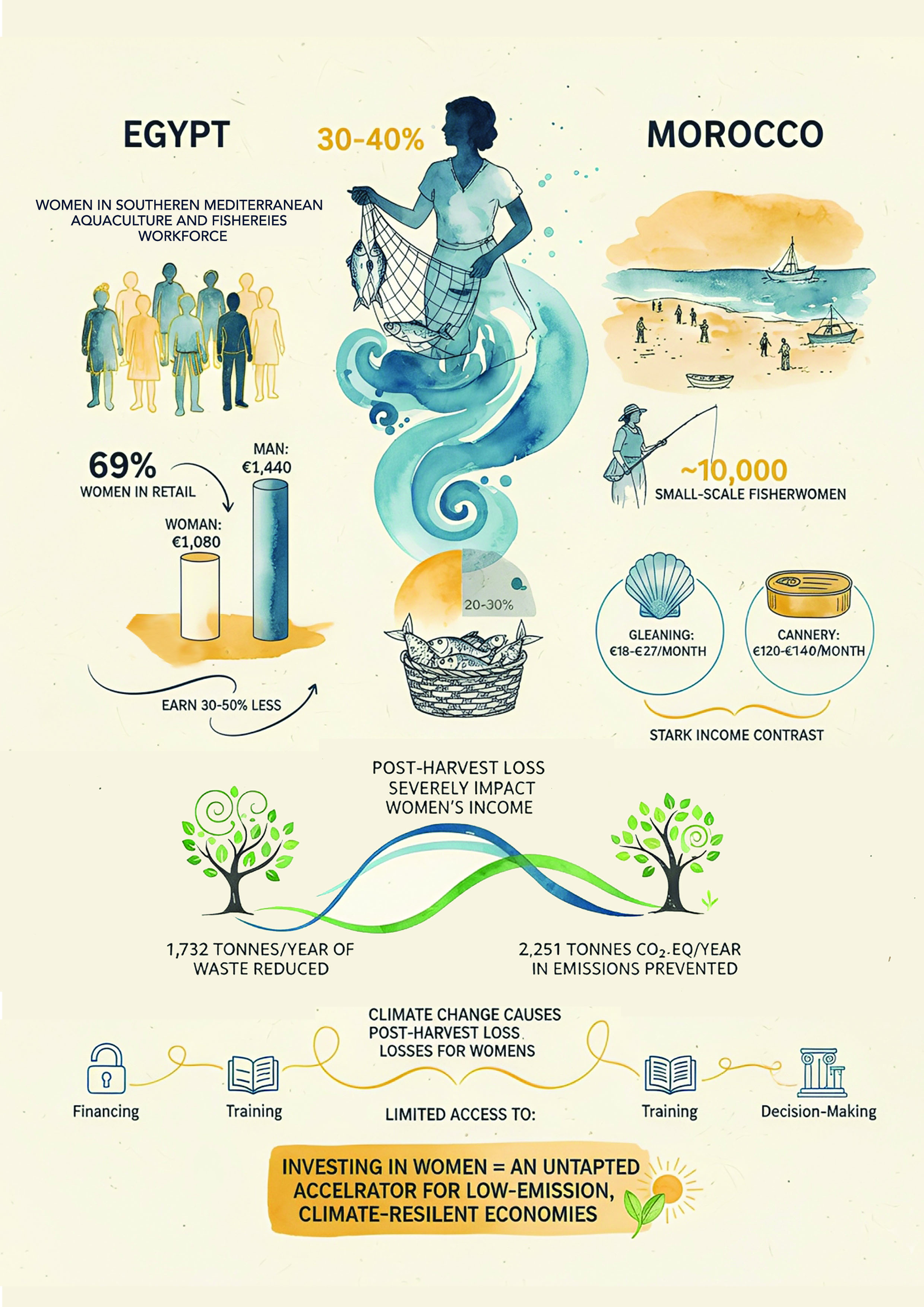

Imagine working every day in a demanding physical job, yet consistently earning 30-50% less than your male counterparts. For the majority of women in fisheries and aquaculture value chains, this is not a hypothetical scenario but a daily reality. A stark paradox lies at the intersection of gender, economy and entrepreneurship: while women constitute up to 40% of the fisheries workforce in the Southern Mediterranean—driving post-harvest activities essential for regional food security and economic sustainability—they remain concentrated in informal, low-paying roles and constrained by deep-rooted social norms and limited access to finance.

Now, climate change is exacerbating these entrenched inequalities. Intensifying heatwaves, which exceed 45°C, are causing fish stocks to decline and increasing spoilage rates. Without access to cold storage or other adaptive technologies, these women bear the brunt of the crisis, experiencing post-harvest losses of 20-30%. This directly slashes their already meagre incomes and threatens household food security across the region.

The Data Paradox

My research into aquaculture and fisheries’ gendered economies reveals a complex reality where challenges are matched by significant, quantifiable opportunities. A forthcoming comparative analysis of women fish retailers in Egypt and small-scale fisherwomen in Morocco demonstrates how gender, location, age and marital status interact to shape distinct economic realities—from the restrictive barriers young Egyptians face in the wholesale sector to the economic c of gleaning activities endured by adult women in Morocco.

Moving beyond these challenges, a trajectory research model of over 500 Egyptian retailers demonstrates that their skilled labour, in cleaning, gutting and processing, is estimated to reduce food waste by 1,732 tonnes annually, preventing an impressive 2,251 tonnes of CO2 equivalent in greenhouse gas emissions.

The path forward demands targeted action. We must replace homogenized interventions with intersectional, gender-responsive approaches. This requires collecting localized, sex-disaggregated data. We cannot manage what we do not measure. Concurrently, we must unlock blue financing through accessible products like micro-loans to help women scale their businesses.

Finally, Euro-Mediterranean partnerships need to embed women’s empowerment at the core of climate resilience strategies. Women must be central to this economy, not supplementary to it.

Acknowledgments

The researcher wishes to express sincere gratitude to her academic supervisor, Ahmed Nasr-Allah (PhD), WorldFish Country Representative in Egypt, for his invaluable support throughout this research. Special thanks are also due to Anna Lindh Foundation’s Mediterranean Youth in Action (MYA) programme team, including anonymous peer-reviewers and experts, as well as the European Union for their generous support. Above all, this work would not have been possible without voluntary participation from Moroccan small-scale fisherwomen and Egyptian women fish retailers, whose testimonies and contributions formed the very foundation of this research.