This blogpost highlights 2020 research outputs of the WorldFish gender theme as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems (FISH). Here, we focus on research examining gender within small-scale fisheries, in particular how social principles emerge and travel, inclusion in biodiversity conservation, and the tracking of gender-sensitive facilitation techniques.

This blogpost highlights 2020 research outputs of the WorldFish gender theme as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems (FISH). Here, we focus on research examining gender within small-scale fisheries, in particular how social principles emerge and travel, inclusion in biodiversity conservation, and the tracking of gender-sensitive facilitation techniques.

Enabling the spread of gender equity

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other global policies and agreements, which set forth the world’s vision for sustainable development, are underpinned by social principles that set standards for best practice.

These principles—including gender equality, human rights, equity, and justice—serve as steady guideposts for steering the world’s efforts. Yet, little is known about how these social principles that are spelled out in global environmental commitments materialize at the national and community level.

Research by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (ARC CoE), WorldFish, and the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), has helped to close this knowledge gap.

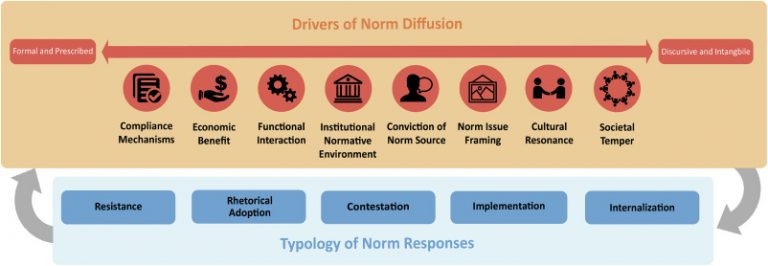

The publication, Rights, equity and justice: A diagnostic for social meta-norm diffusion in environmental governance looks at the different drivers and responses that shape the spread of social principles, and why in many cases they fail to trickle down and shape local action.

“There is a range of factors—or drivers—shaping how these social principles play out in any given society. These drivers range from the formal, such as laws set by governments, all the way to taken-for-granted invisible beliefs and attitudes in different social and cultural settings,” said lead author Sarah Lawless, Ph.D. candidate, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University.

These drivers are received and acted on differently by people or groups working in governance. “For instance, there could be total pushback against an idea or complete adoption of it, which affects if and how the desired outcome is achieved,” said Lawless.

The research provides insights into how the global principle of gender equality is spread, including how it is contested or blocked.

“Our analysis suggests its spread may be hindered by resistance—if the principle was seen as foreign and imposed or out of step with established interests, ideas, and practices,” she said.

“In other cases, we found the principle can evolve, whereby individuals and groups are able to discuss and adapt what gender equality may look like and consist of at regional, national, and local scales of environmental governance.”

The findings, published in Earth System Governance in June 2020, provide a tool to explore the factors that may enable or hinder the spread of different social principles.

This is particularly useful in cases where environmental governance agencies may lack the willingness, resources, or knowledge to meaningfully put these principles into practice, said co-author Andrew Song, a research fellow at UTS.

“If people buy into, accept and endorse these social principles, that’s a win—what we call ‘successful diffusion’,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean they just accept them without questions and pick them straight off the virtual shelf! Different people and societies take them and shape and bend them to fit into their already established beliefs and practices.”

“For example, the translation of the gender equality principle into national fisheries policies and practice has been found to vary across countries due to different interpretations by local actors.”

Song said that incorporating these drivers and responses into future research and policy processes could help to improve the rationale, speed, and mode of the uptake of social principles in environmental governance.

“This is key to achieving sustainable development at scale and enabling environments and societies to flourish,” he added.

Incorporating gender into biodiversity conservation

In recent years, commitments to gender equity and equality are being seen more and more in the global environment and development agenda—partly in response to the targets set within SDG 5 that work to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

Yet, it is not uncommon for biodiversity conservation, climate strategies, and fisheries and aquaculture initiatives to take an overly simplistic view of gender and this has consequences for outcomes.

“For instance, gender is about the rules of play and expectations that society sets for women and men. Yet, it’s sometimes confused with biological differences between males and females, or taken to mean a focus on women only,” explained Dr. Jacqueline Lau, research fellow, working with WorldFish and ARC CoE. “This narrow view risks promoting inequitable processes and might lead to ineffective outcomes.”

Research by Lau outlines three insights that initiatives, policies, and investments can adopt to tackle gender inequality.

“Firstly, it’s important that these efforts engage with the concept of gender and not only with women. This includes recognizing the impact of cultural expectations—what makes men ‘men’ and women ‘women’ in different places?” she said.

“Secondly, not all women and men are the same. It’s critical to factor in how a person’s gender identity intersects with other identities. For example, in Tonle Sap, Cambodia, women with relationships to powerful men in the village are involved in fisheries management, but women in female‐headed households are not.”

“Thirdly, people’s identities mean different things in different circumstances, and so does their treatment. For example, a fisherman’s experiences are very different out on the water with other fishers, compared to in a board meeting with a fisheries department,” said Lau.

The findings draw on insights from feminist political ecology—the field that has developed and continues to investigate ideas around gender, power, and the environment.

“Deeper engagement with these insights can help advance the approach taken by fisheries, aquaculture, climate change, and conservation to how gender is understood, framed, and integrated,” she said. “This supports organizations working in and around fisheries to make meaningful strides toward gender equity and equality, rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach.”

The research, Three lessons for gender equity in biodiversity conservation, was published in Conservation Biology in February 2020.

Lau said the findings will contribute to more inclusive and equitable collaborative management of fisheries and marine resources.

“These insights can help natural resource managers design for and evaluate gender equity by reflecting on how initiatives themselves might reinforce gendered experiences and power relations,” said Lau, also an author of Gender equality in climate policy and practice hindered by assumptions published in Nature Climate Change in March 2021.

“Gender isn’t only something you work with—gender shapes the ways we work and experience the world in all professions, be it in conservation, natural resource management, or climate change.”

Tracking gender-sensitive facilitation in community-based fisheries management

In the Pacific Islands, women are actively engaged in a range of fisheries and fisheries-related paid and unpaid work. As such, for both effectiveness and equity, women’s voices need to be heard in fisheries decision-making processes.

“This is recognized in a new song for coastal fisheries strategy (‘Noumea strategy’) as fundamental to achieving equitable community-based fisheries management, whereby people who rely on a natural resource can determine how it is used and managed,” explained Dr. Danika Kleiber, formerly a research fellow with WorldFish and ARC CoE, and now a social scientist at NOAA Pacific Island Fisheries Science Center.

“When government or non-profit sector actors engage communities in community-based fisheries management set up and planning processes, they must use deliberate, thoughtful, and reflexive strategies to reduce the risk of exacerbating existing gender and social power imbalances,” she said.

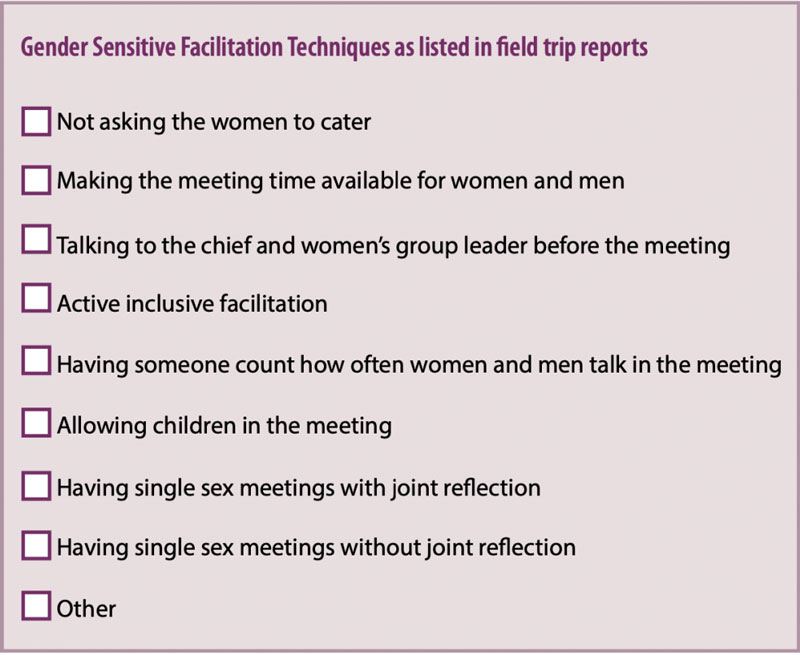

To help facilitators be more gender-inclusive in this critical work, WorldFish developed gender-sensitive facilitation techniques in 2019. This was through the Strengthening and scaling community-based approaches to Pacific coastal management in support of the New Song (‘Pathways project’) funded by ACIAR, the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

“These techniques are designed to recognize barriers to gender equity in community meetings, and suggest facilitation practices that can increase inclusivity,” said Kleiber.

The techniques have been endorsed by the Pacific Community (SPC), the principal scientific and technical organization in the Pacific region, and continue to be scaled by WorldFish and partners.

As a companion, the Pathways project has been testing a simple way to systematize self-monitoring of the use of these gender-sensitive techniques by CBFM actors. Field trip reports completed by project members have featured questions on the techniques and other gender-related objectives since 2017.

“This guides and supports team members who are working with communities to observe and critically reflect on how gender-sensitive their own practices are in the field,” said Chelcia Gomese, Senior Gender Research analyst, WorldFish, in an SPC Women In Fisheries Information Bulletin #32 article.

“The use of these gender-sensitive facilitation techniques, as well as reflections on their efficacy, are important to capture in monitoring and evaluation processes so that they can be improved and scaled appropriately.”

Analysis of the field trip report responses in 2018 and 2019 found there was an increase in the use of gender-sensitive facilitation techniques such as not asking women to cater, talking to the chief and women’s group leaders before the meeting, and allowing children in the meeting.

To increase gender reporting in future field trip reports, Gomese recommended that teams working with communities allow staff enough time for trips to record the number of times men and women speak in meetings, train staff on the importance of gender-specific observations, and ensure staff is aware of local cultural norms in communities.

Research and resources coming soon

In 2021, the WorldFish gender team has research and resources coming out that complement and build on this 2020 work as part of FISH. Highlights to watch out for include:

- Lawless, S., Cohen, P. J., Mangubhai, S., Kleiber, D., & Morrison, T. H. (2021). Gender equality is diluted in commitments made to small-scale fisheries. World Development, 140, 105348.

- The gender chapter of the Illuminating Hidden Harvests study, led by Danika Kleiber and Sarah Harper (University of British Columbia), will highlight the gender dimensions of small-scale fisheries. Learn more in this SPC Women in Fisheries Information Bulletin article.

- An inclusive CBFM framework and assessment methodology to assess inclusion/exclusion in CBFM.