Science is rich with stories. Every dataset, every field trip, every publication and report contains at least one good story. The hard part isn’t finding them, it’s knowing which story will land with which audience, and why some barely cause a ripple while others make waves.

At the recent International Federation of Agricultural Journalists Congress in Nairobi, WorldFish ran a 50-minute session called Looking Beyond the Fields for a Sustainable Planet: The Power of Aquatic Foods. The goal was simple enough, convince a room of agricultural journalists from around the world that the future of food doesn’t just grow on land, that we need to look beyond the fields to see the full picture.

The challenge was to get a room of agricultural journalists to see aquatic foods as part of the bigger food-systems story, echoing what one researcher calls the “out-of-sight, out-of-mind” invisibility of aquatic foods.

Sara Bonilla, a WorldFish Gender Scientist, began with a quiz that revealed how central aquatic foods already are to global diets and livelihoods, and that aquatic foods are among the most climate-smart and nutritious foods we have. Esther Magondu followed with examples from Kenya’s coast from the Asia–Africa BlueTech Superhighway (AABS), where women and youth are running small enterprises through mariculture and integrated aquaculture. Then fish farmer Maxwell Kenga told the story of how science is supporting the community’s work on the ground.

The session drew plenty of interest, but the real value came afterwards in conversations around the WorldFish AABS booth. When asked what makes a good science story, most journalists said they want to show what difference the work makes now, not what it might do one day.

They want to see where change has already taken hold and most importantly, hear from the people behind it, the scientists, the fishers, the farmers, the government officials, the partners and others who make it happen. They’re looking for stories that plug into what’s already going on in the world, an issue already in the news, a shift in policy, a cultural moment or a change people can feel.

Journalists want to place the science in context and show how it fits into the world their readers already recognize.

Making the Invisible Visible

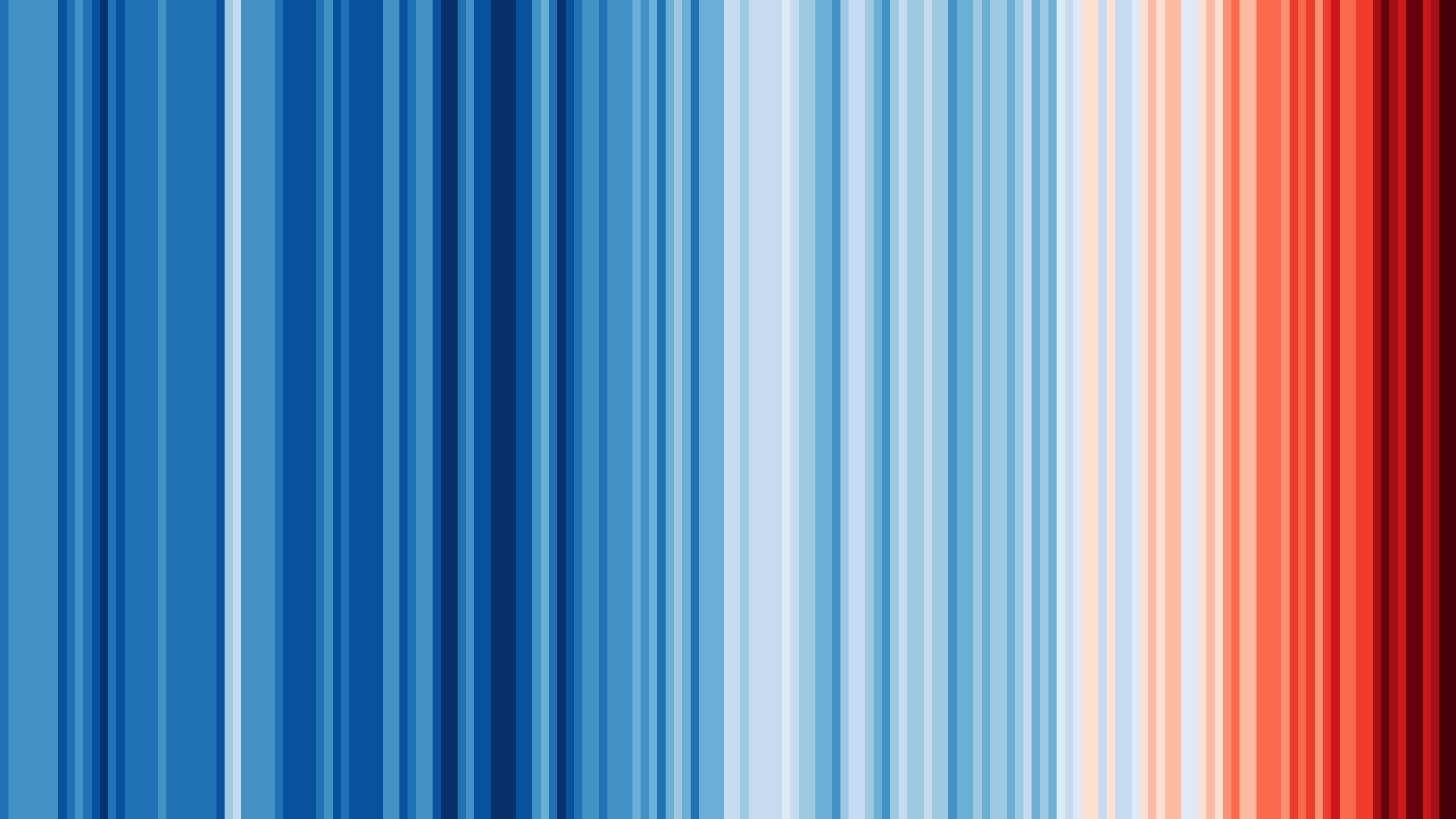

The moments when science cuts through don’t always depend on new discoveries or innovations. They can also happen when someone shows what’s been there all along. The warming stripes, a set of blue-to-red bars created by climate scientist Ed Hawkins, turned more than a century of temperature data into an image that captures and conveys just how fast temperatures are rising.

The Svalbard Seed Vault is another example. Carved into Arctic rock and regularly covered in the media, the vault represents the stakes of losing biodiversity and its critical importance to preserving the future of humanity in a way no report chart ever could.

Of course, not every breakthrough media moment is visual, but every good one has a hook, a moment, a voice, an image or an idea that captures people's attention and sustains it.

Aquatic food systems need their own version of these, moments that make the media sit up and take notice.

Gleaning the Meaning

Back at the conference, in a later session focused on gender, Sara Bonilla vividly described the daily routine of women gleaners in Mozambique while pointing to a beautiful photo of them at work on a beach. It vividly brought to life the ‘why’ behind the work she is doing through AABS and gave the work meaning in a way that data or a report never could.

There’s no formula for a perfect science media story, but there’s a pattern that’s worth paying attention to. The media are looking for stories that fit how the media works. News values tension, consequence and change, not the process or potential. The best science stories make people care. They show change, consequence and meaning.

And while many of the people who sustain aquatic food systems, the fishers, gleaners, processors and traders, remain largely unseen in the media, our challenge is to bring them into view, so their work is rightly recognized in public narratives as central to how the world eats, earns and adapts to change.